Drought Fuels the Spread of Fungi Making People Sick Across California: Study

A new study has found that drought conditions caused by climate change have been behind the spread of dangerous airborne fungi across California in recent years.

Cases of the flu-like illness Coccidioidomycosis—also known as “Valley Fever”—have surged significantly over the past two decades, tripling from 2014 to 2018 and then doubling again from 2018 to 2022, according to the study published on Tuesday in The Lancet Regional Health – Americas journal.

While the illness can lead to severe or even fatal complications, the authors noted that they have identified specific seasonal patterns that could help public health officials prepare for future outbreaks.

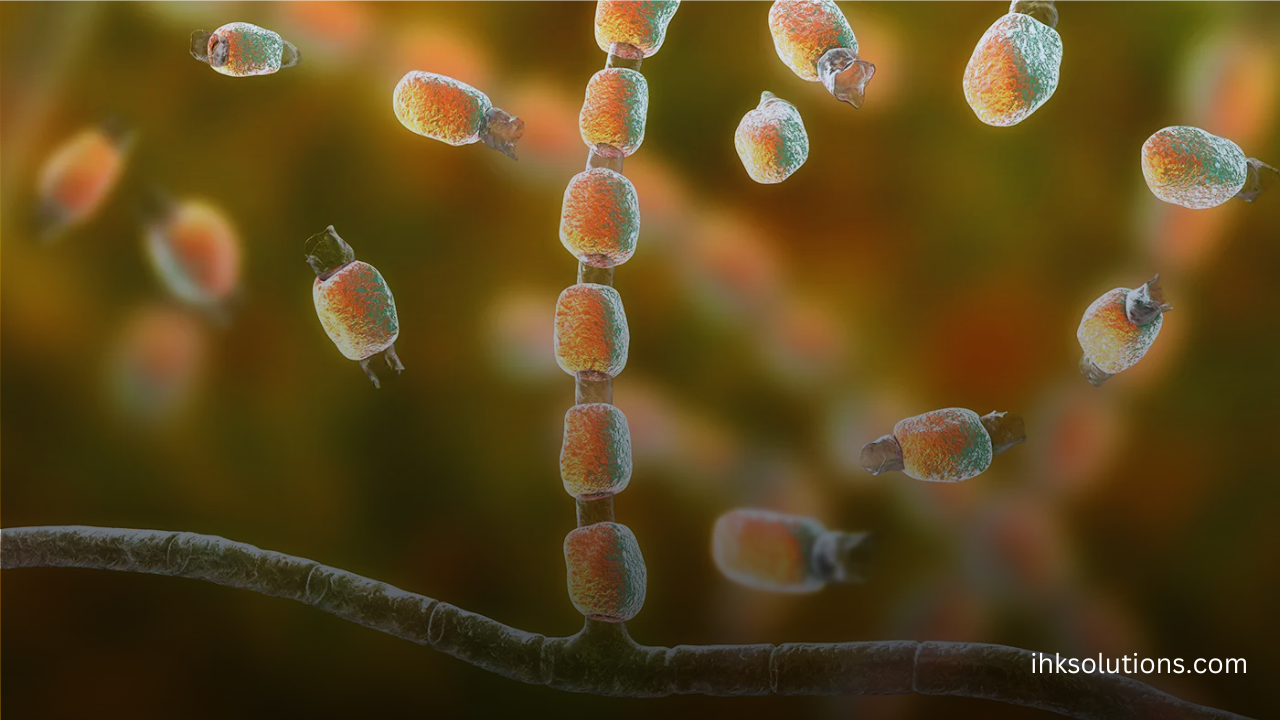

Valley Fever spreads through a soil-dwelling organism called Coccidioides, which was previously concentrated in parts of Arizona and the lower San Joaquin Valley in California. The disease develops not from person-to-person transmission, but from direct inhalation of these fungal spores.

The people most at risk of inhaling the fungi include farmers, field workers, construction crews, or anyone who closely interacts with soil outdoors.

In collaboration with the California Department of Health, a research team led by the University of California analyzed all reported cases of Valley Fever in California from 2000 to 2021. Through two decades of data, the researchers were able to pinpoint how Valley Fever patterns were often driven by drought.

Although most cases tend to occur between September and November, they found that the seasonal behavior and timing showed notable differences between counties and years.

“We were surprised to see that certain years experienced little to no seasonal peak in Valley Fever cases in some counties,” said Alexandra Heaney, Assistant Professor of Climate and Health Epidemiology at the University of California, San Diego, in a statement.

She continued, “This made us question what was driving these differences in seasonality between years.”We realized the timing and began to wonder if the drought could be playing a role.”

Heaney and her colleagues found that, on average, counties in the San Joaquin Valley and the Central Coast regions showed the most pronounced seasonal peaks. However, these peaks occurred earlier in the former, which is California’s agricultural heartland.

During the drought periods themselves, the scientists found that the seasonal peaks in Valley Fever cases were less intense. However, once the rains returned, cases surged significantly—especially in the year or two following the end of the drought.

According to the study, one hypothesis for this pattern is that the heat-resistant Coccidioides spores might be able to outlast their less resilient competitors.

This means that when the rains return, the fungi can multiply as moisture and nutrients become widely available, the authors explained.

Another hypothesis the researchers considered is that drought might lead to increased rodent mortality, and the bodies of these rodents, in turn, provide essential nutrients for the fungi, enhancing their survival.

While drought might initially seem to lower the number of Valley Fever cases, the long-term effect is actually an increase, particularly as we face more severe and frequent droughts.droughts due to climate change,” Heaney said.

Despite the risks of the illness—which can severely affect not only the respiratory system but also the skin, bones, and brain—the researchers identified proactive ways for workers to protect themselves, such as reducing time spent outdoors during dusty periods and wearing face coverings.

Heaney and her team are now expanding their research to other hotspots for Valley Fever, focusing particularly on Arizona, home to about two-thirds of Valley Fever cases in the United States.

Heaney emphasized that understanding when, where, and under what conditions Valley Fever spreads is essential. This knowledge helps public health officials, doctors, and the public take necessary precautions during times of heightened risk.